c/o wesleyan.edu

As many students have heard, Wesleyan was one of the first in the nation to admit women, only to end coeducation and effectively kick them out in 1909. Most know little beyond that, however, about the women who made history by joining what was then an all male, de facto all-white Methodist college.

Although many remain perplexed by Wesleyan’s abrupt coeducation, latent sexism and strong resistance to admitting women at Wesleyan and colleges across New England doomed the first effort at coeducation to fail. The efforts of influential alumni and benefactors along with the Methodist ethos of teaching men and women together were the only support Welseyan’s first women had. By the end of the 19th century, that support had nearly disappeared, leaving gender parity on an unequal and dusty shelf until the mid-20th century.

While black and Jewish students began entering into the student body in more significant numbers in 1965 under the legendary Admissions Director John “Jack” Hoy, women were not readmitted until 1968. During a turbulent time at Wesleyan and the country at large, a special committee agreed to “be recommitted to the admission of women to programs leading to the BA degree,” according to historian David Potts, citing a letter from President Victor Butterfield to the Board of Trustees in his book, “Wesleyan University: 1910-1970, Academic Ambition and Middle Class America.”

A century earlier, Wesleyan had considered admitting women for the first time with an eye on Oberlin, the first all-male school in the country to co-educate. While Oberlin was certainly forward-thinking in admitting female students before any other school in the United States, the details of the plan were disappointing for those who desired true gender parity in education.

“Although almost all the classes women attended were coeducational, fewer than 20 percent of the women graduates up to 1867 earned a B.A. degree,” Potts writes. “A large majority received a diploma from the four-year ‘ladies course,’ which omitted Greek, calculus, and most of the Latin required for a B.A. degree.”

At the risk of imposing contemporary values on the past, the reasoning behind the first model of coeducation in the country was quite sexist by most standards.

“When extolling this two-track approach to a group of educational leaders in mid-1867, James H. Fairchild, President of Oberlin, emphasized the wholesome influence of women students upon their male peers, noted a downward trend in the already small percentage of women seeking the B.A. degree, and found this trend quite natural and appropriate given the separate sphere of duties to which women would ‘properly be called,’” Potts writes.

Unfortunately, the attitudes toward coeducation were no better, if not worse, at most New England colleges. Bates was an outlier as the first New England college to co-educate in 1863, with many New England schools such as Bowdoin, Dartmouth, Trinity, and Yale refusing to even consider admitting women during the following decades.

“In this chilly climate for coeducation in New England, Wesleyan’s treatment of the issue minimized debate,” Potts writes. “After Calef’s resolution of 1867 there is no indication of the topic being discussed during the next four years.”

In testimony before Congress in January 1871, suffragette and former presidential candidate Victoria Woodull argued on the basis of the 14th Amendment that “the broad sunshine of our Constitution has enfranchised all.” Yet not even constitutional grounds could make most New England schools budge.

In 1871, Wesleyan finally joined Bates, Colby, and the University of Vermont in co-educating. Wesleyan leaders used the admission of women as a chance to update the school’s charter. According to Potts, the charter was revised to include a single governing board and specified denominational control and the election of trustees by patron conferences and alumni.

Arthur B. Calef ’51 was an instrumental figure in Wesleyan’s coeducation and charter rewriting. He had reviewed Oberlin’s coeducation report, written by Fairchild, and was able to gain leverage over opponents by arguing that if Wesleyan was indeed only for men, it could have been stipulated as such in the charter at any point.

Orange Judd, one of Wesleyan’s largest benefactors at the time and whom Judd Hall is named after, pitched his policy decision to the Board of Trustees in a resolution that read, “that there is nothing in the Charter or By-Laws which precludes the admission of ladies.”

With that and an official announcement, the University was co-educated. So, why did it take so long? Potts analyzes enrollment statistics among peer schools to explain the delay in Wesleyan’s coeducation.

“Where enrollments at Colby and the University of Vermont were at a low point prior to coeducation decisions, those at Wesleyan were healthy and increasing,” Potts writes. “Wesleyan’s president [Minister Joseph Cummings], although a supporter in principle of education, predicted that coeducation would bring at least short-term reductions in overall enrollment at a time of financial stringency.”

Judd and other prominent Methodists led Wesleyan to move swiftly forward with coeducation. The day before Judd made his motion of coeducation to the board, Judd Hall was dedicated in his name. Coeducation formally began in 1872.

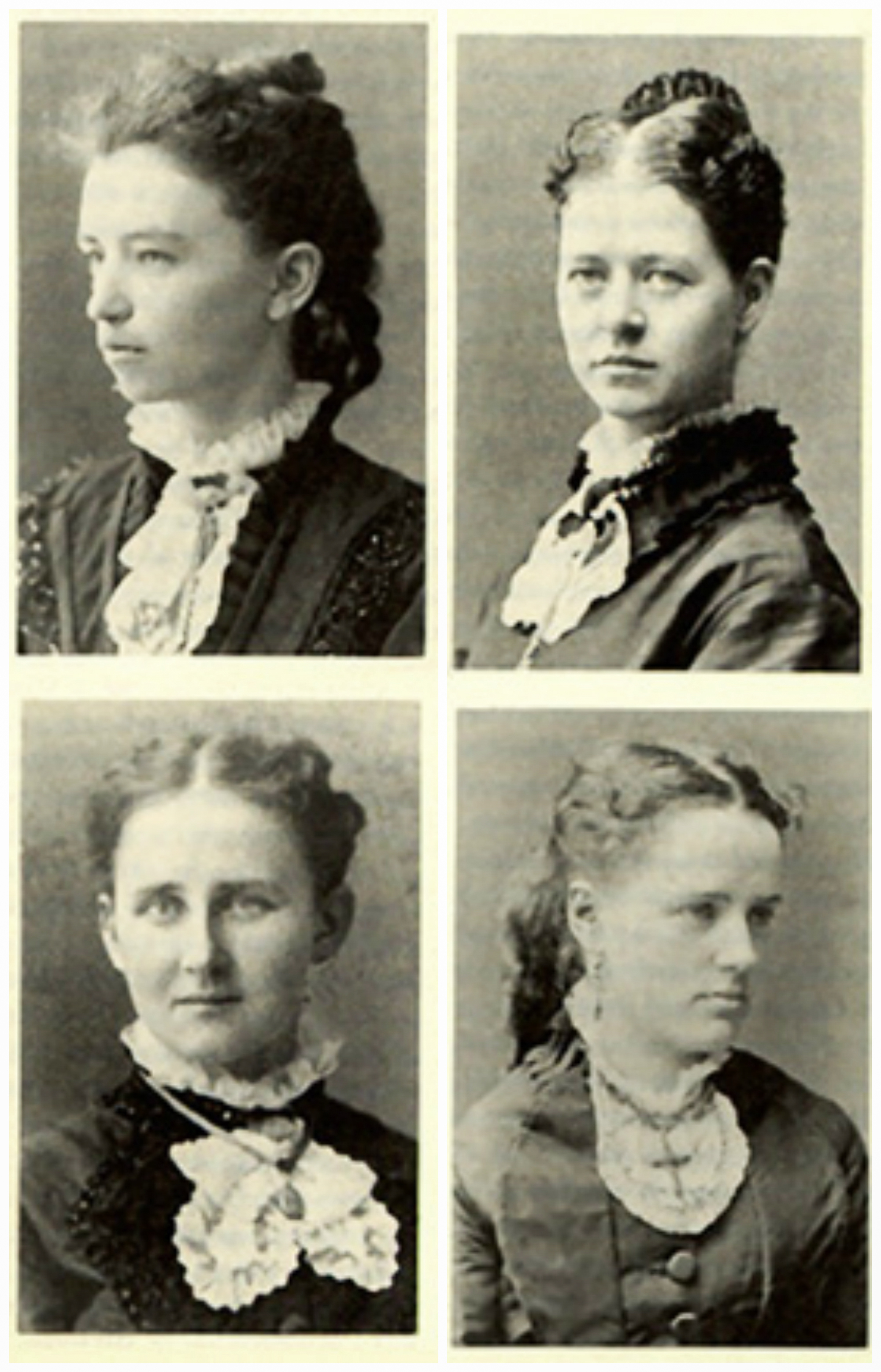

The Methodist tradition of educating boys and girls together was the driving force behind Judd’s efforts to coeducate Wesleyan, but the first four women to graduate from the University were by no means treated as equals. Jennie Larned, Phoebe Stone, Angie Warren, and Hannah Ada Taylor were the first four women to graduate from Wesleyan in the class of 1872. Until 1889, women weren’t allowed to live on campus, and rooms in much of Middletown were not available for women to live without men. Nonetheless, all four of the first female graduates were outstanding students. They all received high honors, graduating Phi Beta Kappa.

Between 1872 and 1892, only 43 women graduated from Wesleyan. Over half of that cohort chose not to marry and went into careers such as teaching, according to Potts and the Department of Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.

After an admissions increase in 1898, campus publications—including The Argus—began excluding women as their number of male members fell. Potts dedicates extensive space to chronicling other ways women were discriminated against at Wesleyan, excluded from certain housing and academic opportunities as well as fraternities, which housed 80 percent of all male students on campus at the time.

By the end of the century, the number of Methodist students at Wesleyan began to fall drastically, and by extension so too did the ethos of coeducation. In 1909, Wesleyan stopped admitting women, prioritizing its transition to a secular institution and the admission of well connected students from the Andrus and Vanderbilt families, for example. Several of the women who weren’t able to graduate as a result of Wesleyan’s reversal of coeducation went on to found Connecticut College, now a staunch rival of Wesleyan and the newest member of the NESCAC.

Although Wesleyan’s first women didn’t get the shot they deserved, many succeeded in obtaining a secondary education following their pioneering journey bombarded by discrimination and double standards.

Comments are closed