c/o squarespace.com

India is undergoing a period of uncertainty. Since February, it has had the world’s fastest growing economy, outpacing that of China. Voter turnout in its 2014 parliamentary election stood at 66 percent, eight percentage points higher than voter turnout for the 2012 U.S. presidential election. Yet it is also plagued by deeply rooted problems of corruption and a continuing conflict between the Indian government and Maoist rebels.

In some ways, India is embracing the American Dream; in others, it is maintaining traditions. Similar to the pro-business attitudes that in some ways created the American Dream, India has become increasingly democratic, while experiencing a rise in income inequality. While many Indians believe that they can climb the social ladder—that they are not resigned to karma, or fate—remnants of the caste system remain.

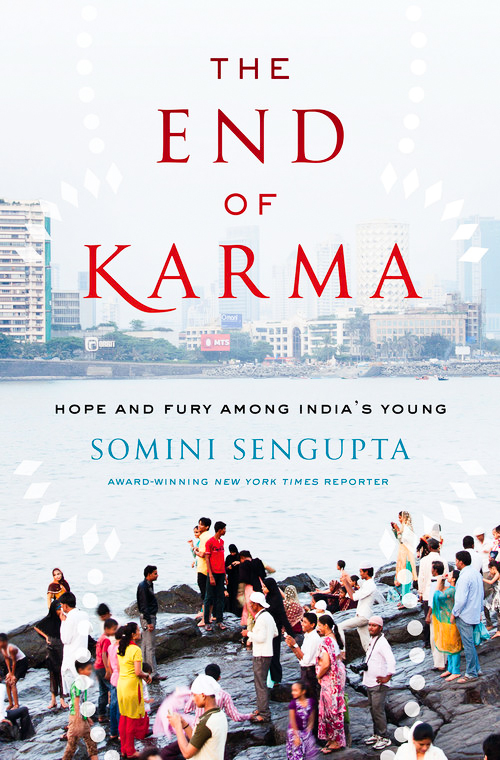

This complicated picture of India emerges in “The End of Karma: Hope and Fury Among India’s Young.” In her book, Somini Sengupta, a New York Times correspondent who currently covers the United Nations and formerly worked as the Times’ bureau chief in New Delhi, profiles seven Indians with a wide range of stories. She traveled to villages and cities to meet with the wealthy, middle class, and poor in order to depict this modern India.

Life in India, as reported by Sengupta, is often full of promise. But just as often, her featured characters express anxieties. In some ways, the new actors achieve successes that, until recently, would have been unavailable to them. In other ways, they are held back by unsurpassable forces.

In one account, new opportunities for education provide more hope than ever for climbing the social ladder. Anupam Kumar is the son of an auto-rickshaw driver but obsessively works his way into one of India’s most competitive universities. The feat was impressive, especially considering the quality of public education in the area. Large numbers of children attend schools but nevertheless wind up functionally illiterate and unable to perform basic arithmetic.

To make it even possible for Anupam to get into college, his mother looked for money to send him to a private school. But even so, when Anupam made it into one of India’s most competitive colleges, his story came as a surprise. Sengupta writes that Anupam’s “picture appeared in the Patna papers: hair greased to one side, eyes shielded by square, unfashionable glasses the face of a boy utterly baffled by having to walk along this new road he had chosen.”

But even then, Anupam had trouble adjusting to the competitive college and was forced to drop out. His ambitious plans for future employment were forced to change.

Through Anupam’s story and others in “The End of Karma,” Sengupta suggests that, as India is increasingly embracing the American Dream, a greater proportion of the population is receiving a chance to improve upon their social position. But at the same time, certain people struggle to climb. In some cases, they became angry and hopeless.

Sengupta’s reporting took her, in one case, to villages where Maoist insurgents were challenging government authority. The people they drew in, she wrote, were “young people who were among the least equipped to survive in the new economy.” Several opposed certain tactics of the insurgents, but the insurgency made them feel wanted.

Sengupta’s reporting throughout is impressive and deep. She travels to both safe and dangerous locations, displaying a wide array of modern Indian life with a great degree of nuance. Whether she is reporting on insurgents or on college hopefuls, she captures her subjects’ humanity.

India, as she portrays it, is in the process of figuring out how to function as a modern democracy. She discusses widespread corruption and government assaults on free speech, while also depicting the love the Indian population has for voting. The variety of her reports creates a nuanced picture of modern India.

The one flaw of Sengupta’s book is that her story often feels too much like a memoir. Sengupta was born in India, and she often discusses her childhood as a way of showing how India has changed since the 1970s. But her stories are rarely as compelling as those she finds as a journalist, and they often add little to the accounts.

That said, the stories she finds provide brilliant ways of discussing 21st-century India. The book is a thorough account of India as it struggles to get rid of a caste system.

Comments are closed