Sage Marshall, Contributing Writer

Although today the University is known more for its student’s progressive views, a more alternative social sphere that accepts New York and California hipsters alike, and a very challenging liberal arts education, the University was once at the forefront of collegiate athletics. The school boasts the oldest continuously used baseball field in existence, and the University’s football and baseball teams competed against teams such as Yale and Harvard. Athletics at Wesleyan served as a masculinizing force. Collegiate athletics originated as a sharply gendered space, and despite the current development of a strong female athletic program, the sexist impact of Wesleyan athletics still remains in Andrus Field.

Today, well over one hundred years after students began playing sports on Andrus Field, the hallmark of University athletics sits in the center of the University. Students mill around, enjoying the spring weather. Despite the older buildings of College Row facing away from the field, new buildings such as the Usdan Campus Center face it, showing its continued importance. The deep green grass of the baseball field is trimmed short and the sand raked. In the coming weeks, many students will watch the games from the comfort of Foss Hill. Unfortunately, the purpose of this central environment has always been and still is only for male sports. Women are excluded from the field, which since its origin has been a male-gendered space.

Andrus Field originated during the late 19th century, a time period when men tried to counteract the shifting gender orders that were caused by urbanization and industrialization. In the early 19th century, women gained power as family farms closed and people moved to work in factories and live in cities. However, to combat these changing gender relations, wealthy white men (like those at top academic institutions like the University) adapted a biologically-based superior identity connected to athletics. Athletics provided an arena to perpetuate the differences between men and women.

Early athletics at the University focused on masculinity. A Methodist University, it adapted values of the Protestant Ethic to athletics, emphasizing hard, manly work. At the groundbreaking for Fayerweather gymnasium in 1894 (which bordered Andrus Field), influential trustee Stephen Henry Olin reinforced these values.

“Here will be formed ideals of manliness and sportsmanship,” he said.

Thus, University sports served the role of helping impressionable young men overcome the “feminizing” effect that was perceived as they lived in overcrowded cities and worked in impersonal large corporations, no longer physically working their own land like their ancestors. Wesleyan’s President Rev. Bradford Paul Raymond mirrored Olin’s statement in 1895.

“The man who goes on the football field is the man who learns to develop the right kind of courage to meet the difficulties of great cities,” Raymond said.

Andrus Field would serve as a place to foster masculinity at Wesleyan through two sports: baseball and football.

Baseball, with the first team organized in 1864, was extremely relevant to the virtuous ideals of sport because, unlike football, it also stressed gentlemanly behavior.

“Baseball may be conducted as a clean and uplifting game such as people of true moral refinement may patronize without doing any violence to conceive,” said William McKeever in his 1913 book, “Training the Boy.”

In fact, in an Argus article published in 1869 the writer took the time to compliment the proper behavior of the players, despite an especially poor performance where the Wesleyan freshmen lost to the Brown freshmen by a score of 22-44.

“[The game] was entirely free from all swearing and quarrels over the decisions of the umpire, and the members of both clubs behaved like perfect gentlemen,” he wrote.

Thus, many religious alumni and University presidents began to place a strong emphasis on the individual participation in athletics, such as baseball.

The rapid evolution of football at the University in the late 18th century provided the impetus for the University to finally build the official Andrus Field and embrace confrontational team athletics as an integral part of the school. Although students had begun playing pickup football on the land that became Andrus Field by at least the early 1870s (and probably earlier), the University did not organize its first team until 1881.

The team used the land that became Andrus Field, still uneven and swampy, because football was a primitive, unorganized game with hardly any rules. In contrast to baseball, football promoted and represented a more animalistic type of masculinity focused on aggression and physicality. During the mid 80s, football evolved into a more uniform game, and the University moved to the forefront of major collegiate football, playing the likes of Yale, Harvard, and Princeton. Thus, in 1892, the University fully drained and cleared the field, demonstrating its acceptance of a physical sport that resembled combat.

Between 1872 and 1912, the University had an early experiment with coeducation, but women were fully excluded from athletics and the male-dominated social sphere. Women were banned from using the gymnasium. This exclusion was connected to a national concern about women’s menstrual cycle.

“Perceived as a pathological condition…[the menstrual cycle] necessitated the exclusion of women from vigorous and competitive sports and from any physical exertion which medical experts considered overtaxing,” Patricia Vertinsky, Associate Professor of Education at the University of British Columbia, wrote.

The societal sexism that was demonstrated through women’s exclusion from athletics was also mirrored in other aspects of University life. Women at the University did not write for The Argus and were not allowed to hold class office. Furthermore, male students called the women “quails,” supposedly in part because they were young women who could be seen as a nuisance or prey. As women were merely tolerated by their male counterparts and excluded from athletics, they were confined by the Victorian feminine ideals of marriage and domestic duty. After the women graduated they would be forced to decide between marriage and career, demonstrating the separation of social power between men and women in the early 20th century.

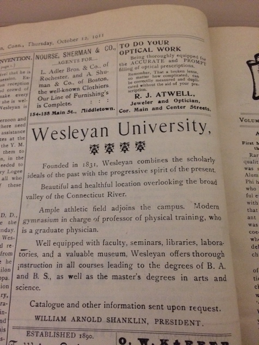

As Andrus Field became an attraction for the University, the male students and alumni saw women as hindering the growth and success of athletics. In 1902, donors funded a grandstand for Andrus Field, and in an Oct. 12, 1911 edition of The Argus, the University took out an ad that promoted the field. Evidently, the University not only accepted Andrus Field as an important part of the campus, but promoted it to attract students. However, during this same time period, male students and alumni were pushing out the small female student population.

“We are the only college endeavoring to claim prominence in athletics that is hampered by the term ‘quail institute’,” said a student-athlete to the Hartford Courant (Dec. 6, 1898) anonymously. “Only last year we lost a star pitcher for the baseball team and this year four crack-a-jack football men, three of whom eventually entered Princeton, owing to their feeling on the matter of co-education.”

Students and alumni vehemently expressed their opposition to coeducation during this period.

“Banish football!… Banish baseball!!” one such alumnus wrote in The Argus on Oct. 19, 1898. “I expect you fellows, excuse me, you girls will soon be sending little pink envelopes to the alumni soliciting subscriptions to the Wesleyan Croquet Club, Wesleyan Sewing Circles and similar organizations. Say, girls, please take my name off the list, won’t you?”

It is not surprising that young men at the University felt athletics were threatened by coeducation. Athletics were supposed to allow men to bond, develop a masculine culture, and separate themselves from effeminate women. Over the next 10 years, women were gradually pushed out of the university, as they posed a threat to the prestige of a school that didn’t want to become like Boston University, an institution they felt became feminized as a result of coeducation.

Currently, the University still promotes Andrus Field for its long and storied history. However, they do not acknowledge the historical sexism that the field provided. Despite Title IX and the creation of other high-level facilities for female sports, women are still excluded from the field. This central feature of University athletics remains as an obviously male-gendered place where women are only permitted on the sidelines. In order for the University to accept women as equal to men, women’s sports teams should be given access to Andrus Field, and the administration must acknowledge the historical sexism that this central environment provided and still provides.

Comments are closed