c/o startribune.com

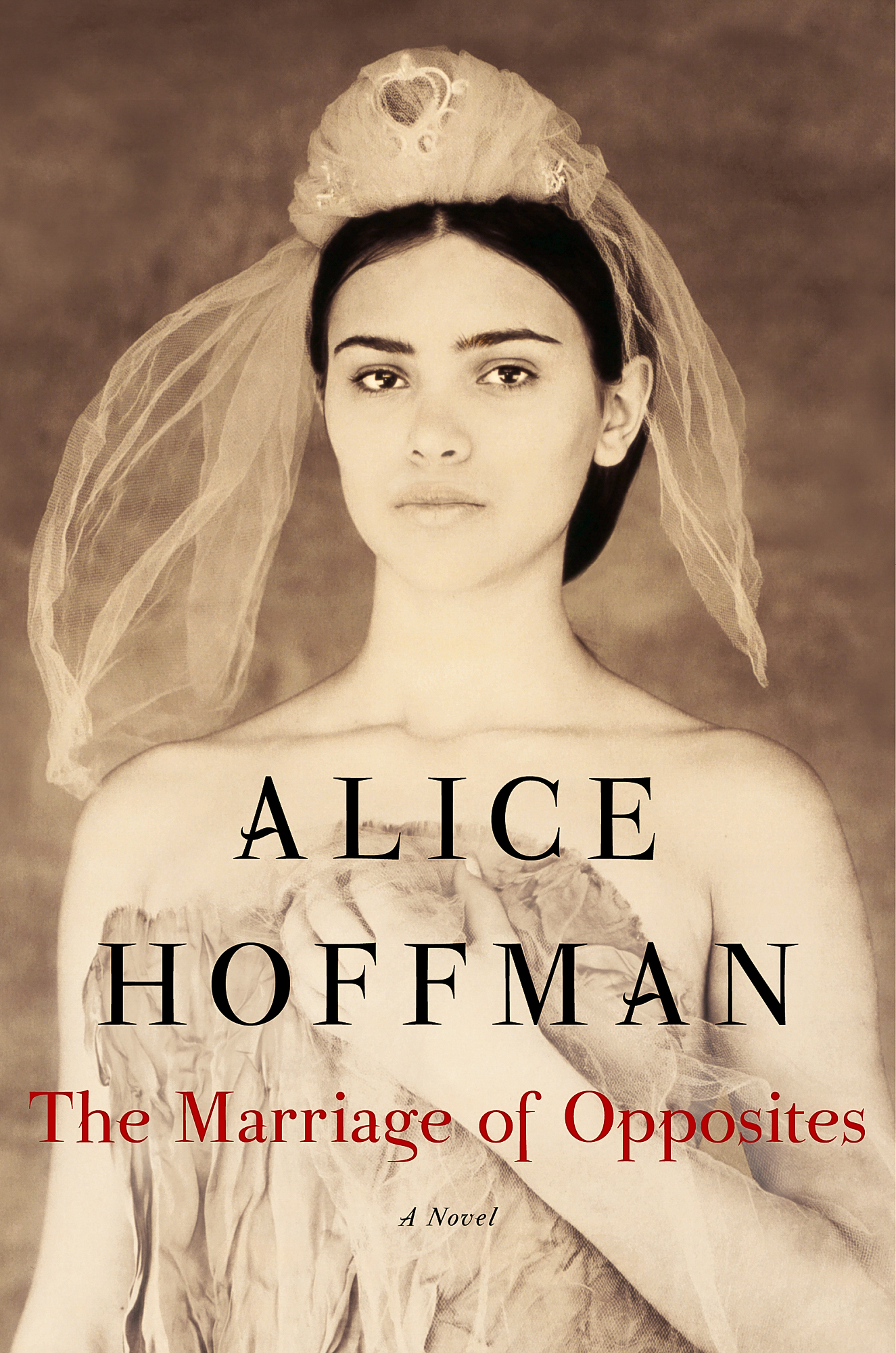

Reading fiction can enlighten an idle reader in two different but overlapping ways: The first is through telling a story at the most basic level, in which we can feel how certain characters feel and consequently identify with them. The second is through telling a story that is, in some shape or form, also based in fact, and that actually happened to characters that have lived on the same planet as us. Put these two together and you get historical fiction, which is history that is not about coverage, but rather depth—history that is not about dates, names, and places, but feelings, problems, and, in the case of Alice Hoffman’s new book, “The Marriage of Opposites,” love.

On the topic of love, it would be dishonest not to mention that I generally don’t fancy love stories. I thought “Love in the Time of Cholera” was an excellent story about love, but I became bored with the romances in “Water for Elephants,” “Anna Karenina,” “The Hunger Games,” “The Great Gatsby,” and even “Romeo and Juliet.” I’m not going to try to justify my claims here, as I think it’s just a matter of taste. But needless to say, Alice Hoffman’s “The Marriage of Opposites” came off to me as sappy in the sections of love, a bit too fluffy for my liking. I will thus not talk about these pages too much, and let other readers come to their own impressions.

Nonetheless, I think “The Marriage of Opposites” is still a book worth reading, mostly because of that second facet of historical fiction—i.e., the history behind its subject. To understand the subject we must first delve into a quick synopsis.

“The Marriage of Opposites” mostly chronicles the life and family of Rachel Pizarro, a Jewish mother living on the island of St. Thomas at the turn of the 19th century. St. Thomas sits to the east of Puerto Rico, and Hoffman goes to great lengths to describe how hot it is there, frequently mentioning that everyone sweats through their stuffy 1800s-era clothing. Rachel is the daughter of a shipping merchant and an overwhelmingly bitter mother, both of whom get ample page space in the beginning of the novel as Rachel grows up. Rachel’s parents aren’t necessarily interesting characters, and much of the first 100 pages of the book seem like a collection of smaller vignettes, detailing Rachel’s early life, in which she devours her father’s books and yearns to live in Paris. The protagonist teeters on becoming the archetype of a woman who dives into books to escape her despair, but Hoffman eventually saves Rachel from this fate after the first quarter or so of the novel.

The narrative seems to hit lift-off when both Rachel’s parents and her first arranged husband pass away, and a young man named Frédéric arrives at St. Thomas to take over her father’s business. Frédéric has a sort of breakneck energy to him, a feeling that “his life is always out of control,” and his giddiness helps to propel the story into Rachel’s early adulthood. The two end up marrying, and not without some difficulty, as Frédéric is Rachel’s first husband’s nephew. But when Rachel finally petitions the Grand Rabbi of Denmark to allow them to wed, Rachel and Frédéric finally get to tie the knot. Over the course of her life, Rachel ends up having seven kids with Frédéric, many of whom are wholly neglected from the narrative; they seem to be born and then whisked away, never to be given any true attention inside the confines of the book.

One of the Pizarro children does get a fair amount of attention in the second half of the novel, though, and for good reason —Rachel is the mother of the wonderful Camille Pissarro, considered a father of Impressionism. Hoffman pulls us into Camille’s story as she shows his hasty development from a defiant schoolboy to a creative genius, an artist who “saw what others did not.” Hoffman has plenty of opportunities to develop Camille as an artist, but she ends up falling short and Camille becomes overshadowed by the bitterness Rachel displays in old age. It is unclear what makes Rachel so resentful of Camille’s career as a painter. Nonetheless, it overwhelms the narrative until the end of the novel.

In Katherine Mansfield’s notebooks, one can find the following bit of juicy literary criticism: “Putting my weakest books to the wall last night I came across a copy of ‘Howard’s End’ and had a look into it. Not good enough. E.M. Forster never gets any further than warming the teapot. He’s a rare fine hand at that. Feel this teapot. Is it not beautifully warm? Yes, but there ain’t going to be no tea.” Hoffman seems to simply warm the teapot as well. There is an enormous amount of opportunity in the history of her subject, with side stories of slaves on St. Thomas and an abducted child living in Paris, but Hoffman seems to care less about these stories and more about a certain portrayal of Rachel as an old woman. “The Marriage of Opposites” tells the story of a lesser-known family history, but it falls short of all that is packed within and around that history. In the end, it fails to crank the heat high enough.

Comments are closed