c/o collider.com

Within everyone is a desire for salvation, for some mythical figure or revolutionary to save humanity from its troubles. Centuries ago, humans found salvation in religious figures ranging from Christ to Muhammad. A few hundred years ago, salvation was present in the ideals of democratic revolutions. In the 20th century, the revolutions morphed into the violent idealism of fascism and communism.

The details change, but the fundamentals remain the same: “If only we could just [fill in the blank], we could end all of our problems!” Most revolutions fail, usually due to some delusional dogma that leads its followers toward pointless violence. But the yearning for a savior, someone who rises above the rest of humanity, who delivers a message of perfection on earth, still remains.

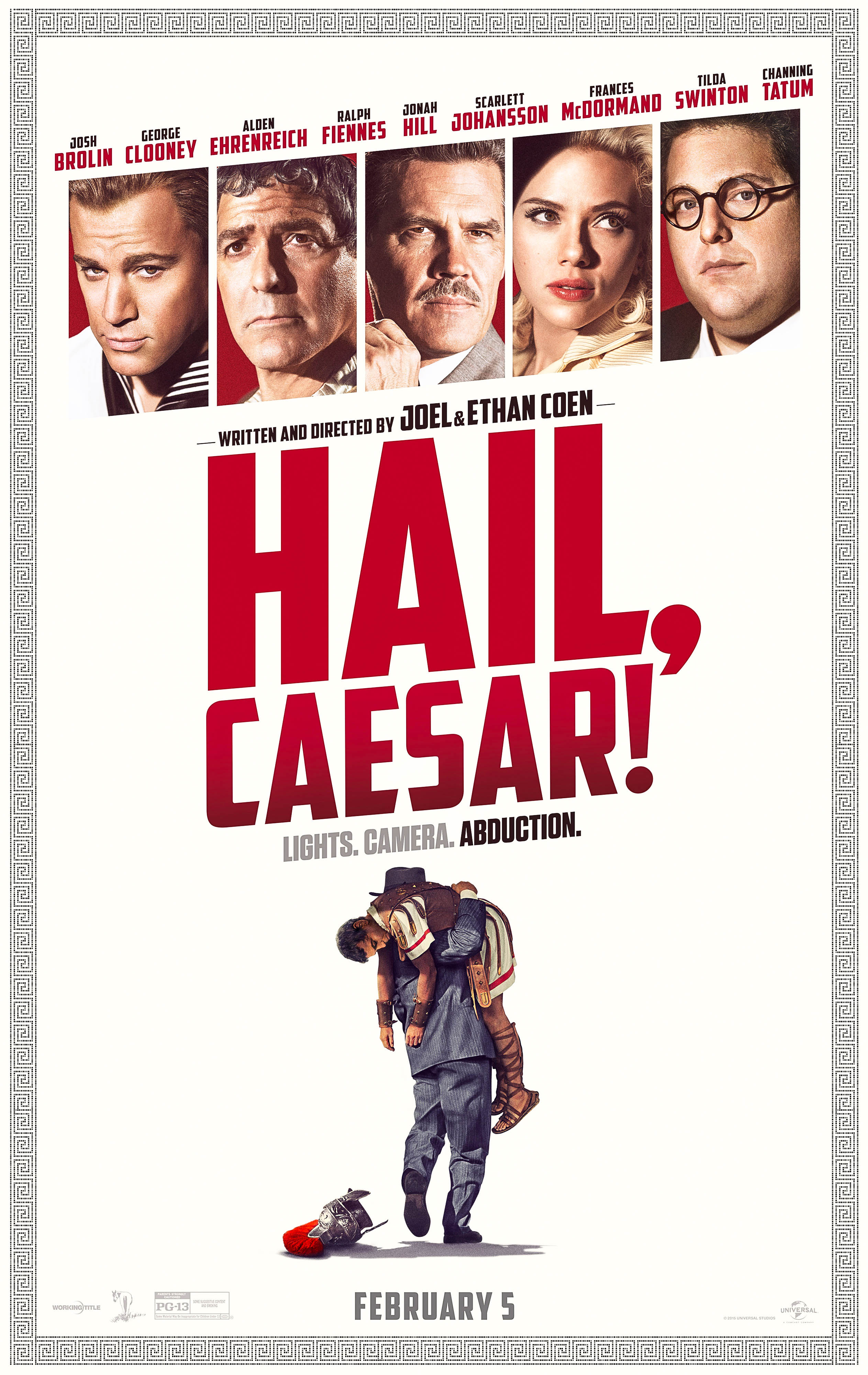

This idea is the thematic crux at the center of “Hail, Caesar!” the Coen brothers’ latest movie. Beyond this broad theme, there is very little that holds together the fabric of the film, and the result is scattered moments of brilliance that add up to an unsatisfactory whole. “Caesar” has the colorful visual quirks of a Wes Anderson flick, and the subtle melancholy of a Charlie Kaufman movie. It has a plethora of celebrity actors, from George Clooney and Channing Tatum to Scarlett Johansson and Ralph Fiennes, yet nearly every major role comes off as a half-hearted cameo. “Caesar” deals in both the glory and nostalgia of old Hollywood, but has little to say about it other than, “Hey, Hollywood was crazy, right?” The film has something big to say about the human condition, but it lacks a plot, compelling characters, and (most surprisingly) good performances.

Set in 1950s Hollywood, “Caesar” follows Eddie Mannix (Josh Brolin) as he stresses over making movies in a timely manner, keeping internal corruption out of the eyes of the press (represented by Tilda Swinton as identical twins, for some reason), and confessing his sins, Catholic style, every 12 hours or so. Mega-star Baird Whitlock (George Clooney) is preparing to star in a movie within the movie, also called “Hail, Caesar,” about a Roman centaur who discovers the Christian god when he’s drugged by an extra and kidnapped by a mysterious, shadowy group.

Shockingly, but not really, his kidnappers turn out to be a group of communists hell-bent on destroying capitalism. (Although this was meant to be a twist, communism is essentially a prerequisite for any movie set in 1950s Hollywood.) The third major plot of the film deals with Hobie Doyle, played by relative newcomer Alden Ehrenreich, a star of Westerns who, much to his disdain, finds himself recast in a fancy drama by Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes, the biggest treat of the film). Themes such as utopia, religion, and nostalgia are meant to connect these plotlines, but alas, they don’t.

The movie’s saving grace should have been its performances, but unfortunately, this was not the case. Brolin, the closest thing this movie has to a protagonist, is quite solid as Mannix, but the Coens’ script doesn’t know if he’s supposed to be a satirical archetype or developed character, and he is therefore neither. Brolin brings subtle anxiety to the role, but the Coens do not allow him to do much else.

The rest of the cast similarly suffers from poorly drawn characters, and for reasons I cannot comprehend, many of them come off as deeply uncomfortable on camera. Johansson, doing her best New Jersey accent, and Swinton each appear in roughly two or three brief scenes, both looking oddly tense and uncomfortable on-camera. Clooney, as a boozy, egotistical star, has practically been handed the chance to play himself, but he never seems at home in his role, either. Considering the talent on and off of the camera, “Caesar” somehow presents audiences with the poor combination of weak characterization and acting.

There are two exceptions: Tatum and newcomer Ehrenreich are absolutely wonderful from start to finish. Tatum is a natural song-and-dance man, positioning himself as a 21st–century Gene Kelly, joyously tapping and singing his way through a musical number pulled straight out of old Hollywood; Ehrenreich captures and sustains a subtle nostalgic sorrow in every scene he’s in, as his profession (an actor in Westerns) slowly becomes irrelevant.

And, while I’m being charitable, I must say that the Coens have done a lovely job directing in every sense not related to their actors. Their scenery is lush and colorful, and their visual direction captures a quiet and tremendous sense of sorrow. Their deliberately unsubtle Christ imagery, from Soviet subs rising from the depths of the sea, to poor Roman citizens gazing in awe at their savior, matched with a grandiose score by the fantastic Carter Burwell encapsulates the underlying sorrow of utopian ideology. In its best moments, “Caesar” is a sensory exploration of the yearning for the utopian and provides moments of startlingly tragic beauty.

In the film’s (and the film within the film’s) climactic finale, Whitlock delivers a rousing speech about how humanity could save itself from its folly. But he stutters on the final lines: “If we only had but…but…uh….”

The director screams, “Cut!” and frustratingly cries, “Faith! It’s faith!” But did faith really help the Soviets? Did it really save the Romans citizens from eternal poverty? No, it did not, and the Coens understand this perfectly; there is no simple solution to end all problems, only the ability to dream them up.

Immediately after this scene comes an abrupt shift in tone and plot: Mannix decides that making movies is his sacred duty, the camera swings upward toward the sun (and, symbolically, the heavens) and cuts to the beginning of the credits…or, more precisely, the Coens’ names plastered across the screen. Because, well, who needs a real ending when one can simply pat oneself on the back for hard work and mediocre results?

“Hail, Caesar!” is not worthy of this blatant self-praise. It could have, and frankly should have been, but it isn’t. Instead, it leaves audiences sighing, lamenting, and shouting to the sky up above, “They could’ve made a great movie, if they only just…just….”

Comments are closed