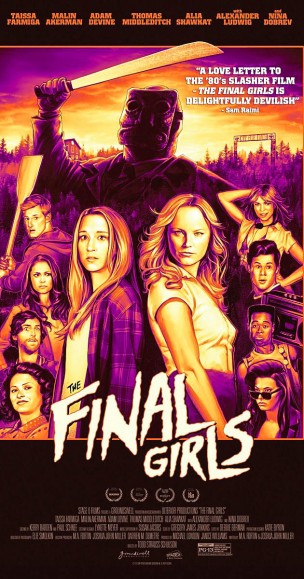

For all its visual flair, "Final Girls" fails to leave a mark.

Maybe it’s because my bar for horror-comedy satires is so high after watching “The Cabin in the Woods,” but director Todd Strauss-Schulson’s “The Final Girls” is a meta-disappointment. Though considering Strauss-Schulson’s only other feature directing credit is “A Very Harold and Kumar Christmas” (the film that killed the trilogy) from all the way back in 2011, I wouldn’t be surprised if the writers of this unenthused script, M.A. Fortin and Josh Miller, could not find anyone else. Honestly, any semblance of wit could have been picked out and made into a short film on Vimeo, like Hasselhoff’s ’80s throwback “True Survivor” (and it probably would have been just as good, especially since “Final Girls” is more interested in polished landscape shots than story or decent jokes).

“Final Girls” lacks both the heart of a film like “Warm Bodies” and the smart, quick-witted writing of “Scream.” If anything, I would compare it to “Tucker and Dale vs. Evil,” due to its lack of scary moments, and the fact that it seemed like it always wanted us to be aware that we are watching a film instead of taking the time to immerse us in it. But at least then Alan Tudyk carried “Tucker and Dale” along with a few laugh-out-loud moments.

If you’re going to make a horror-comedy, the most important aspect is a smart script with an ingenious premise that’s also funny. Maybe it’s just that Strauss-Schulson is biting off more than he can chew in his attempt to portray a heartfelt mother-daughter relationship inside the campy ’80s slasher, but besides the presence of Thomas Middleditch (who, shockingly and sadly, isn’t even in half the film) and some picturesque purple-hued lightning-filled exposition shots at the film’s climax (which is out of place for an ’80s slasher), there’s little to enjoy.

A prologue shows Max (Taissa Farmiga) driving home with her B-movie-actress mom, Amanda (Malin Akerman), when the obligatory car accident ensues. You just know that whenever a scene takes place in car, it’s only to set up an accident. At least in films like “Whiplash” or “No Country for Old Men” the subsequent actions that the characters take is engaging. Here, the crash is just to move the plot along. Immediately after, we cut three years later to show Max without her mom. The car is like a character in and of itself, with a ticking time bomb. It’s not the Hitchcockian suspense of whether or not they will make it out of the conversation alive, but instead a matter of when. Strauss-Schulson seems somewhat self-aware of the audience’s intelligence by having Akerman turn her head back and forth from her daughter to the road, with the audience on the edge of its seat, expecting the crash to come at each swivel.

Coincidentally, we jump ahead three years to the anniversary of Amanda’s death, which is the day Max goes to see “Camp Bloodbath,” the film-within-the-film starring her mother. She goes along with her friends: Vicki, who shockingly befriends the other two females just before she dies (Nina Dobrev); Chris, the athletic, Chris Hemsworth wannabe (Alexander Ludwig); Max’s best friend Gertie (Alia Shawkat); and cinephile Duncan (Thomas Middleditch). Mid-“Bloodbath,” the classic fire in the theater occurs, and the characters are forced, with the exits blocked, to cut a hole in the screen and exit through the schlocky celluloid flick. Once they enter, the line between fiction and reality is blurred and it’s unclear whether the characters’ dialogue is bad because they’re in an poorly-written ’80s slasher, or simply because the film’s own script is flaccid. With lame, recycled jokes like, “Maybe it’s Jewish heaven,” or “I’m sticking to that bitch like white on rice,” it’s a wonder that this film actually made it to VOD, let alone to theaters.

Another problem, though, and what sets this film apart from influences like “Scream” and “The Cabin in the Woods,” is not only the directing and the writing, but also the cast: Alexander Ludwig is no Chris Hemsworth. Luckily, Fran Kranz’s bona fide double, Thomas Middleditch, successfully transfers his geeky mannerisms over from “Silicon Valley” to give this film some life. But for some reason, the writers decide to hardly use him. As a rule, actors playing characters within movies are always more melodramatic than the actors outside of the film-within-a-film. But the level of acting from half the ensemble foreign to “Camp Bloodbath” is so low (barring Farmiga, who gets her solid acting chops from her older sister) that it detracts from our ability to connect with them. Maybe it’s just the fact that they’re all playing high school seniors, instead of college kids, but for at least the first 15 minutes of the film or longer, they all seem just as insecure speaking the dialogue as the writers must have felt about it when writing the script. The writing on the whole could have been from a couple of high school kids that don’t have enough talent or empathy to create interesting characters.

Strauss-Schulson’s attempt at creating emotion through the mother-daughter relationship is flawed from the get-go. One of the sparingly few jokes that hit the mark, decidedly given to Middleditch, is his critique of the Divine’s joke arsenal, a microcosm of ’80s slasher humor, when he jokingly remarks, “The writing is so bad.” How then, if I might ask, is it that “Camp Bloodbath”’s Nancy is able to attempt to become a three-dimensional human being? Yes, they repeatedly make it a point to make the audience know that she’s “just the shy girl, with the clipboard and the guitar,” but that doesn’t mean she isn’t a flat character; something of which Max should have also taken note. And if the two aren’t so different after all, the audience shouldn’t feel any sympathy for Amanda when she’s frustrated that she can’t do any better than gigs for campy slasher films.

Ultimately, if you’re a fan of ’80s slasher films, and you want to see a deconstruction of the genre mixed with a touching, albeit flawed, mother-daughter relationship, you should probably check it out regardless of this review. Gregory Jenkins’ pop-synth score is decent, at least.

Comments are closed