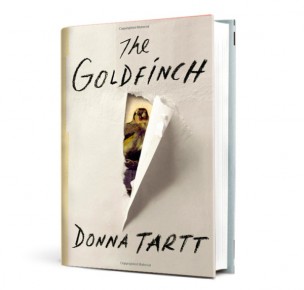

Though it appears at first to be a simple coming-of-age tale set in Manhattan, Donna Tartt’s recent success, “The Goldfinch,” is a story that traverses continents and time periods. The story is one of deep emotional unraveling and eventual victory.

Though it appears at first to be a simple coming-of-age tale set in Manhattan, Donna Tartt’s recent success, “The Goldfinch,” is a story that traverses continents and time periods. The story is one of deep emotional unraveling and eventual victory.

Coincidentally, the novel was released on the heels of the opening of an enchanting exhibit at The Frick Collection in Manhattan titled “Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals: Masterpieces of Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis.” Notable pieces on display included “The Girl with the Pearl Earring” (1665) and Carel Fabritius’ small masterpiece, “The Goldfinch” (1654), after which the book is named.

The novel opens with an introduction to Theo Decker, a 13-year-old boy traveling to the Metropolitan Museum of Art with his single mother right before a meeting regarding his suspension from school. They admire his mother’s favorite piece, Fabritius’ masterful rendering of a yellow goldfinch perched on its feed box and, puzzlingly, chained to it.

When I visited The Frick over winter break, I understood Mrs. Decker’s impassioned attraction to the painting. Though it is not much larger than a personal mirror, the painting is vibrant with color, perfectly capturing the essence of the bird’s multicolored wings, its sleek head, and its deep, dark eyes. The bird looks out on the world with a glint of omniscience. The single yellow streak in the wing provokes a notion of surprise, as if the bird might take flight at any moment. I almost pictured it flying toward me right off the canvas.

The most curious aspect of the painting, however, is the single gold chain around the bird’s foot, an object intended to baffle its audience. Why is the bird kept imprisoned in this way? Why is it robbed of the chance to experience the world?

In the novel, Theo and his mother are in the museum, looking at the painting with great interest, when a bomb explodes, killing Mrs. Decker and countless others and destroying a host of valuable paintings. Theo miraculously survives the explosion; from under the rubble, he uncovers the Fabritius painting, still intact. Adolescent intuition prompts Theo to take the painting with him, though he does not fully understand the potential consequences of his actions. He is simply attempting to salvage a relic that represents the end of the first chapter of his life; now, he must care for it with the help of neither of his parents.

Before the explosion, Theo becomes entranced by a young girl with fire-red hair at the museum. She is chaperoned by an older man, Welty, who touchingly and painstakingly explains little-known facts about the work on the walls, demonstrating a deep emotional attachment to and sense of responsibility for the girl. After the explosion, the older man dies at Theo’s side and gives him his ring, which Theo returns to Welty’s business partner, Hobie.

Theo’s life becomes nomadic. For a time, he lives with the family of his old friend, Andy Barbour, on the Upper East Side, a clear representation of the stereotypical moneyed existence that seems bleak and too crisp to envy from the outside. His father eventually appears with a Las Vegas tan and a drug addiction to replace his previous alcoholism. Xandra, his father’s leggy, low-class girlfriend, also arrives on the scene.

Theo unwillingly moves to Las Vegas with his father and Xandra. At school, he befriends Boris, a skinny, precocious boy originally from the Ukraine who has lived all over the world. With “small, gray teeth” and an insatiable appetite for literature, booze, and adventure, Boris piques Theo’s interest. The Decker clan and Boris create an unlikely family.

But in a sudden, horrible instant, Theo’s father is killed in a car accident, and Theo leaves Boris behind to return to New York, moving in with Hobie and eventually becoming his business partner. Dangerous business with the stolen painting, which Theo has been harboring for years, later takes him to Amsterdam, where he discovers both the downfalls of the drug world and the possibility for a brighter future.

“The Goldfinch” is richly textured and nuanced with real struggles of drug addiction and familial loss. It is also a tale of resilience, of finding the best way to survive and perhaps even thrive in the wake of unspeakable loss. Though it is at times exhaustively descriptive, with too many characters to count and perhaps a few hundred pages too many, the novel still had me hooked the whole time. The single thread that unites the story, the stolen painting, is what makes it a story of humanity and triumph even through great struggle. Just like the captive finch in the painting, Theo manages after many years to escape the shackles of his life’s circumstances and find a means of survival.

Comments are closed